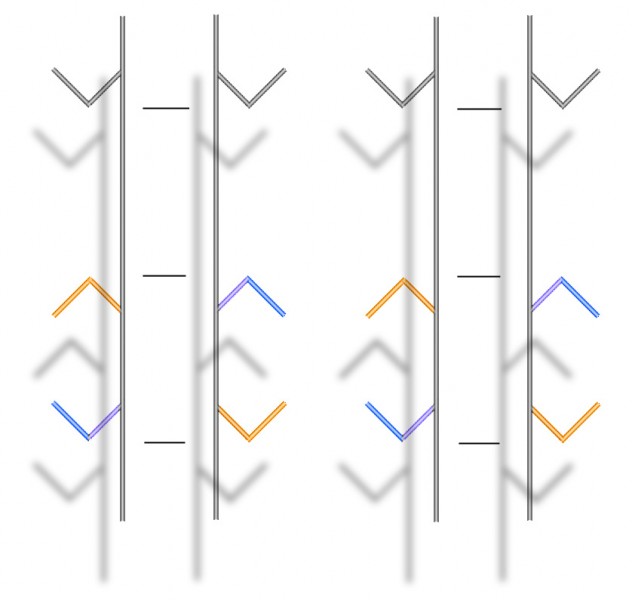

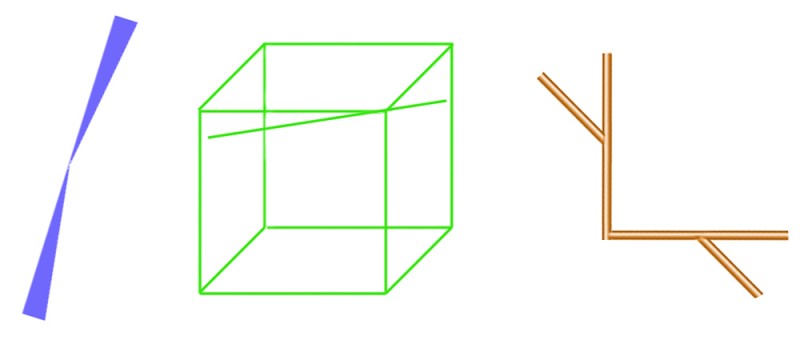

Here are three rather subtle illusions, each showing bent lines. In Bourdon’s illusion, to the left, the straight left hand edge looks bent. In Humphrey’s figure, centre, the straight, loose line touching the corner of the cube looks bent. And in the figure to the right, the straight line interrupted by the corner looks bent. I don’t think we really understand any of these illusions, and they are not very dramatic, so you don’t see them often. When someone does puzzle them out, for sure they’ll be a key to subtle ways the brain works. There’s probably a different explanation for each. For example, both the left and middle figures show a bent line that is the backbone of two triangles meeting at a point, so you might think, hello hello, we’re getting somewhere. But then you notice that the lines bend in different directions in relation to the triangles each illusion.

If you like to tangle with the technicalities, there are learned studies of the Bourdon illusion and the corner figure, though unfortunately, you’ll only get an abstract of the articles on those links, unless you are in a university library where they subscribe to the journals. And you won’t find much on Humphrey’s figure anyway, it’s seriously obscure.

Here’s a bit more on the corner figure ….