Here’s a movie of a brilliant, double spiral novelty illusion ring. It’s available to buy from Grand Illusions, and on that link you can also see another movie of the illusory effect. As the ring is rotated, it seems to expand when rotated one way, and contract when rotated the other way.

It just may be a version of the kind of ring described in one of the oldest reports of an illusion to have come down to us – a description by the French commentator Montaigne, written nearly five hundred years ago. In an essay called An Apology for Raymond Sebond he describes …

….those rings which are engraved with feathers of the kind described in heraldry as endless feathers – no eye can discern their width, or defend itself from the impression that from one side they appear to enlarge, and on the other to diminish, even when you turn the ring around your finger. Meanwhile if you measure them they appear to have constant width, without variation …..

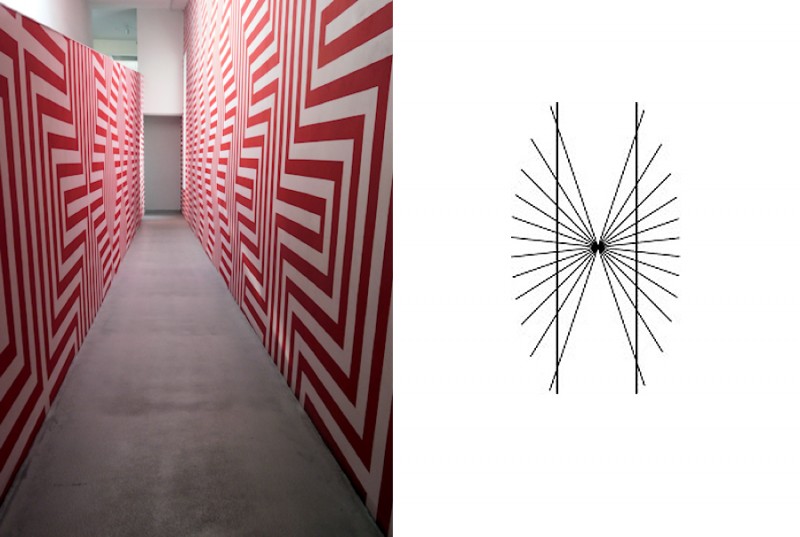

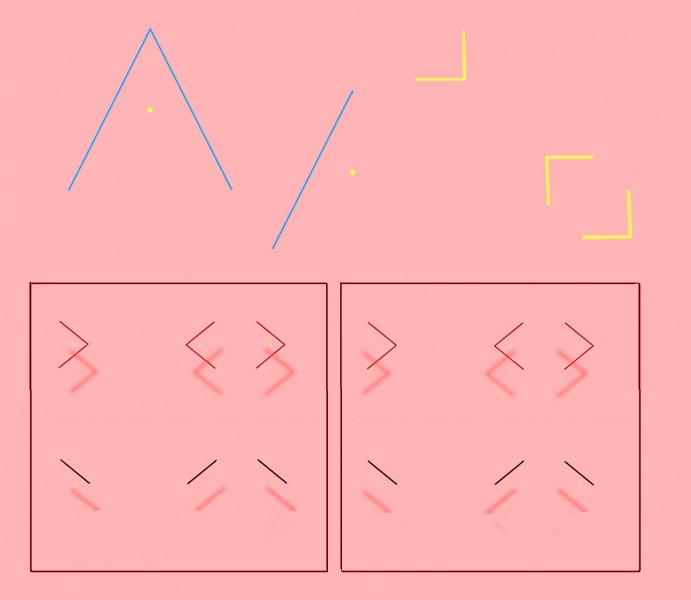

Researcher Jacques Ninio quoted that extract in his 2001 book The Science of Illusions (page 15), noting that a design on a ring like the one below looks wider at the top than the bottom, thanks to the Zollner illusion but is objectively the same width all the way along.

All the same, Montaigne’s description of rotating the ring makes me wonder if that’s the whole story. So I’m on the hunt for surviving mediaeval rings that might decide the issue. And meanwhile, though there are theories about how the Zollner effect arises, no researcher as far as I know has an explanation for the effect shown in the novelty ring available from Grand Illusions (and other suppliers). I reckon it’s to do with the way that the highlights expand or contract with rotation, but then seem to carry the outline of the object with them. This is a puzzle which I will be coming back to.