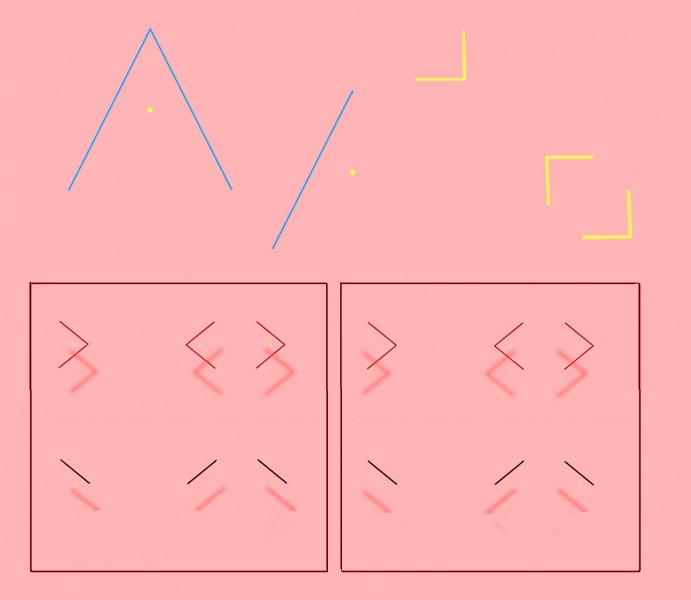

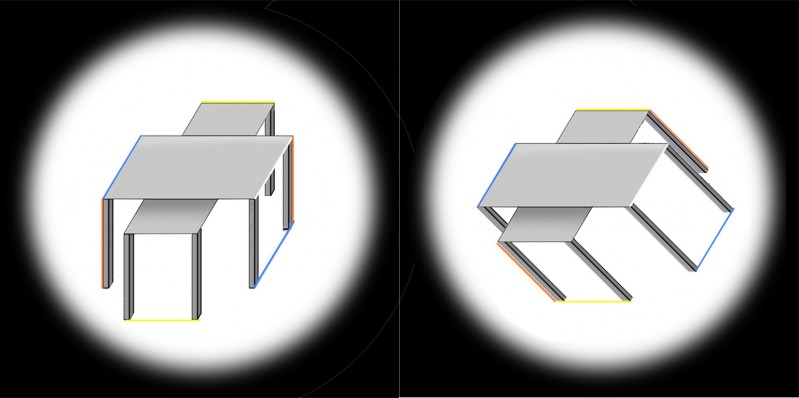

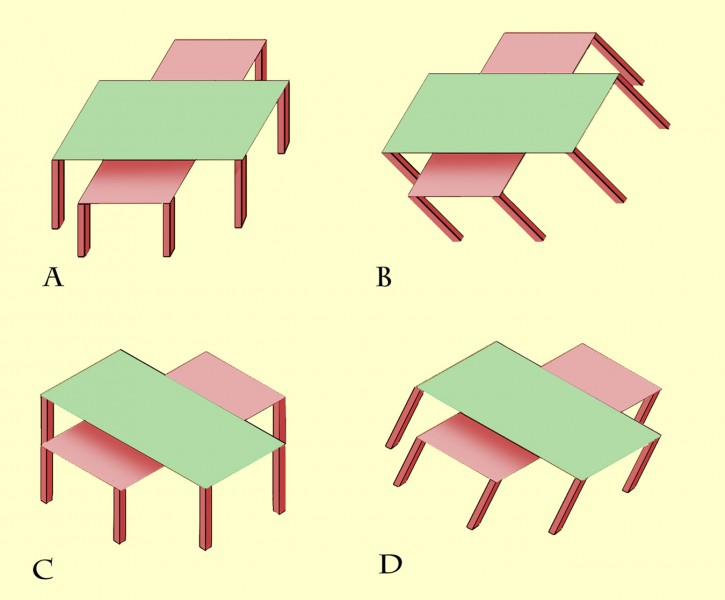

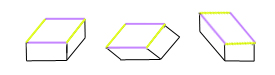

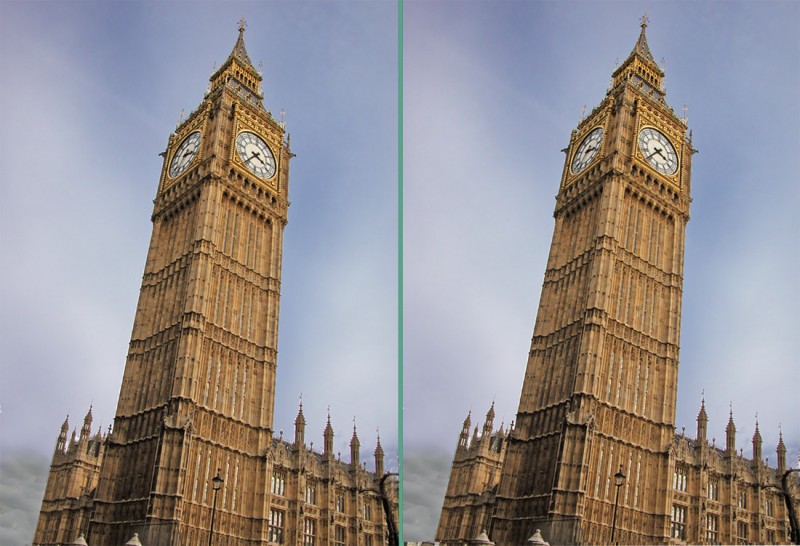

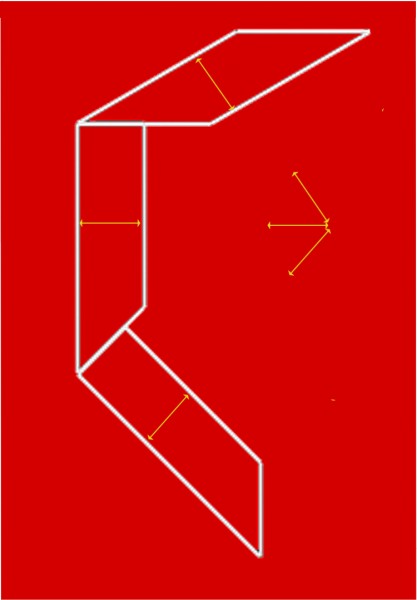

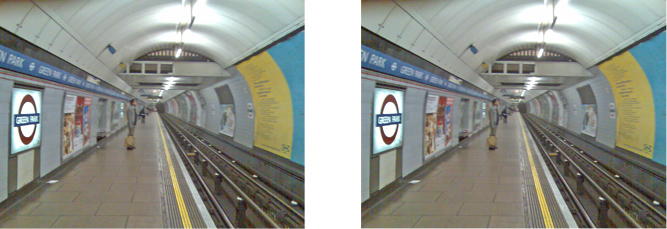

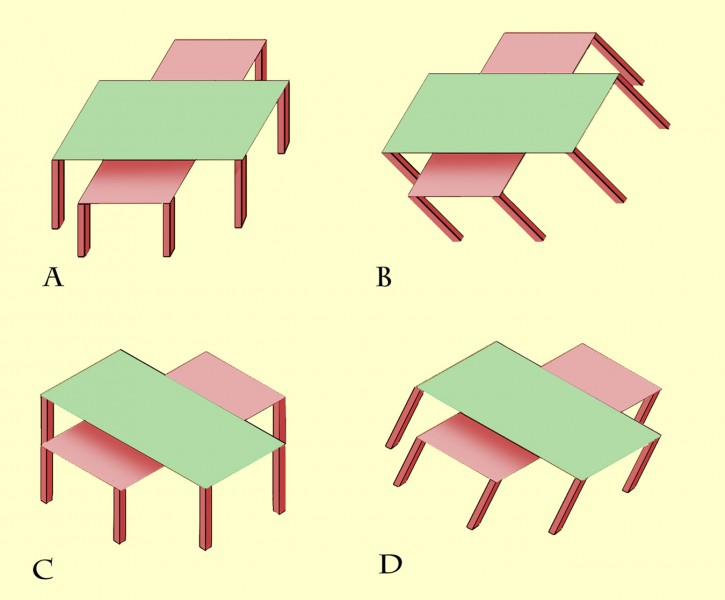

The previous post presented an animation of Shepard’s Tables. If you didn’t see that, you might want to check it out first (scroll down to the previous post) to get the basics of the illusion. This new version of the illusion, with nested tables, follows the pattern: all eight of the lozenge shaped table-tops are identical in shape, but the more that a lozenge is seen with its long edge parallel to the line of sight, the more it looks long and thin as it stretches into the distance. The more it’s seen short edge parallel to the line of sight, the more it looks wide and stumpy.

Describing the illusion that way may explain a puzzling variant of Shepard’s Tables, recently reported by Lydia Maniatis, as mentioned in the previous post. As the problem appears in these nested tables, at B the edges of the table-tops that are horizontal on the screen must be receding into depth, and yet they don’t show the dramatic illusion of a stretch into depth that we see in the edges receding into distance at A. Why not?

Isn’t it a question of perspective? At A the horizontal table edges are represented as if seen head on, parallel to the image plane – the plane at right angles to our line of sight. The table edges that are oblique on the screen at A must therefore be extending into depth in the most extreme way, parallel to the line of sight and at right angles to the image plane. Seen like that, depth effects are maximised. At B, no edges are aligned with the image plane, and all the edges, even the ones that are horizontal on the screen, are receding at 45 degrees to the line of sight. That’s a much less extreme recession into depth. So although the table edges that are objectively horizontal on the screen at B are receding, they don’t show as much illusory stretch into depth as the receding edges in A.

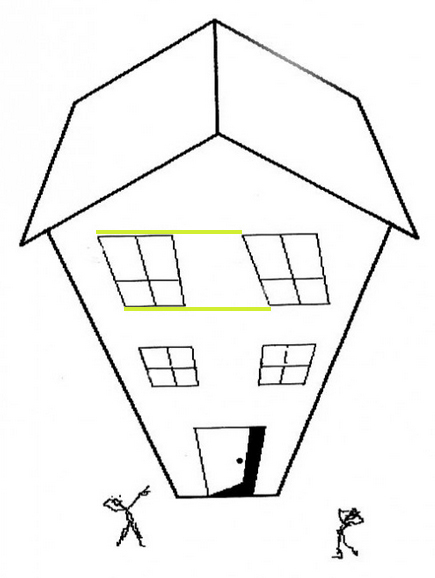

Lydia Maniatis observation raises a general point that’s really interesting – the way that appearances can depend on what we mean by “up”.

Continue reading →