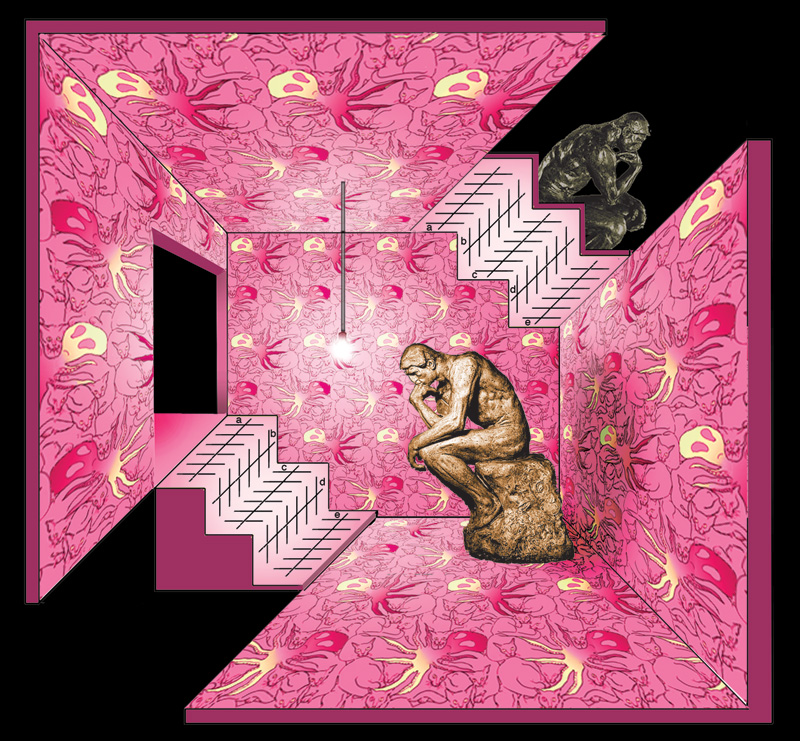

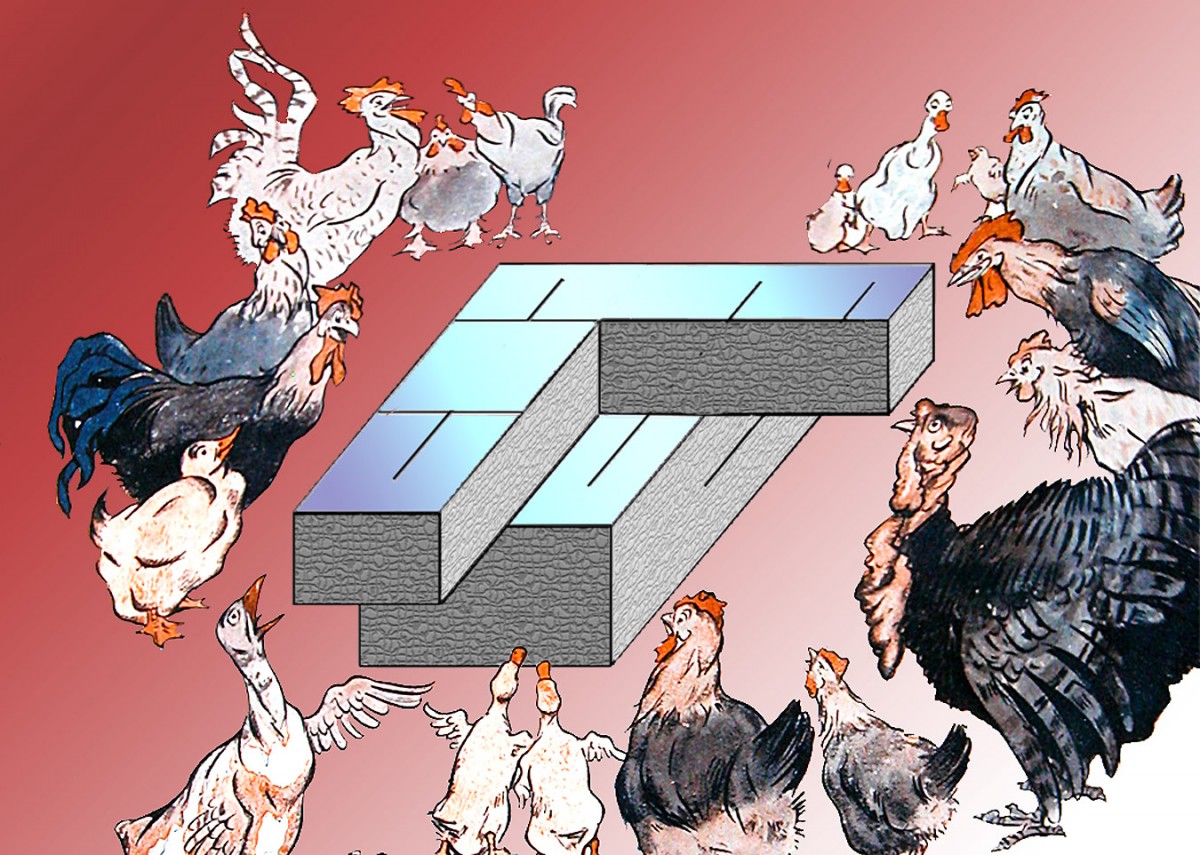

Size constancy is the term for our tendency to see distant objects as larger than they are. So the far end of a shape with parallel sides looks wider than the near end. (See the earlier post on The Wonky Window). It seems to be such a basic feature of vision that it can give rise to amazing effects. In the photo, first note note that the “sculpture” is impossible! All four blocks are receding from us, so they could only connect up in real space as a bendy snake. Instead they join up in an impossible, ever-receding, endless loop. (See the earlier post on M.C.Escher’s Waterfall for how that kind of impossible figure works). Here the endless loop leads to a paradox, thanks to size constancy. The distant end of each block seems wider than the near end, and yet at the same time seems to be exactly the same size as the apparently smaller, near end of the next block. Measure the sides of the blocks and you’ll find them parallel. It’s one of many demonstrations that perceptual space is not always geometrically consistent, (or it can be non-Euclidean, as the specialists put it).

I located my impossible sculpture in a deeply receding space because that makes the effect just a bit stronger.

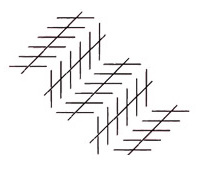

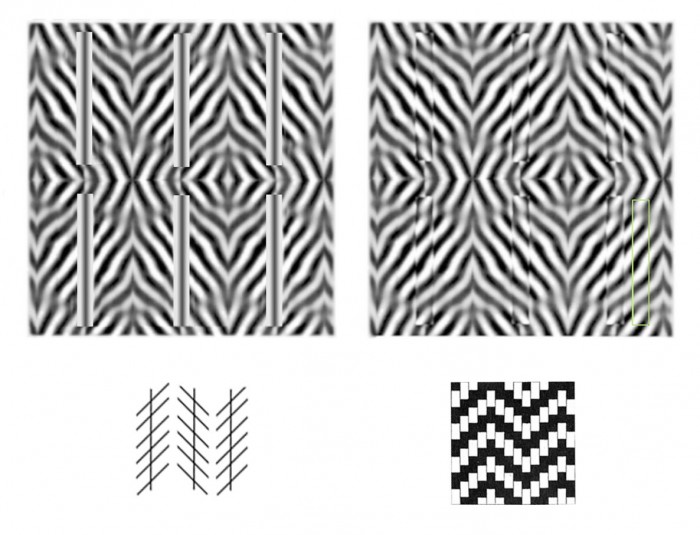

Update January 2010: How could I have overlooked this? The stripes I’ve added to these blocks will be enhancing the effect of divergence by adding the chevron illusion to the size-constancy effect. The chevron illusion was first reported 500 years ago, by French writer Montaigne, as related in Jaques Ninio’s book on illusions, page 15. The chevron effect is a special case of the illusion later re-discovered a bit over a century ago as the Zollner illusion. Some specialists would say both effects depend on the brain’s attempts to make sense of figures as shapes in space. I suspect that’s true of the size-constancy effect, but that the chevron effect is 2D, pattern driven. That seems supported by the observation that whilst in the picture above the chevron and size-constancy effects are acting in consort, they can also oppose one another, reducing the effect of divergence.

Read on for more on size-constancy.

Continue reading →