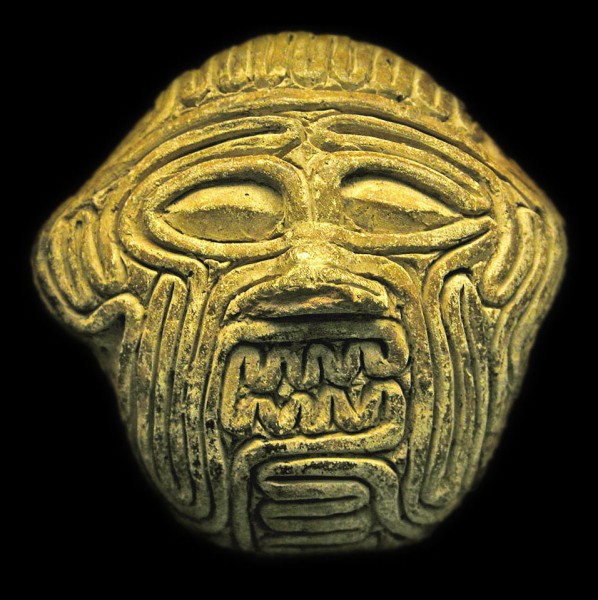

Eyespots are fascinating. Nature presents all sorts of camouflage and mimicry, but mostly when prey species look like harmful species, or are camouflaged against background, or imitate leaves, or when seahorses look like seaweed (sea dragons). The imitation then is in 3D, like a waxwork. But eyespots are nature’s only example of patterning that becomes a picture. Eyes in real life tend to be quite rounded and beady or bulging, but butterfly eyespots are flat. Yet they can be amazingly convincing, like the ones at the top of this picture of a peacock butterfly, complete with illusionistic highlights.

And apparently birds really are deceived by the eyes. A study five years ago by Adrian Vallin and colleagues at Stockholm University demonstrated that butterflies with eyespots covered up really are much more likely to be eaten. Apparently, the Peacock butterfly tends to rest with wings folded, looking a bit like old leaves, but when threatened suddenly spreads its wings to reveal this alarming mask. It even makes a noise as well.

But when you look at lots of eyespots it gets more puzzling. For example, the eyespots that are top in this picture look very realistic, but then the ones lower down are a bit of a mess. Generally, looking through pictures of lots of eyespots, there’s the same spectrum from very illusionistic to very approximate. Do they all work in the same way? And then, the most illusionistic eyespots of all are maybe the ones on the underneath of the wings of the owl butterfly. But birds only see those when the butterfly has its wings folded, so that only one eyespot is visible. (Or does the owl butterfly lie on its back with its wings open when it’s depressed?).

So when the birds are frightened by eyespots, are they just responding to a stimulus on the retina that’s a bit like the pattern of stimulus from real eyes, so that even appoximate eyespots will do? If so, why have some eyespots evolved to be so illusionistic? Maybe the messy spots, like the ones lower down my photo, are transitional forms. But if the illusionistic eyespots, complete with highlights, are more effective, can we then say that the birds are being deceived by pictures? I don’t think there’s another example of a non human unequivocally understanding a picture. Reflections in a mirror, yes. That was established amongst others by by Frans de Waal of the Yerkes primate research centre in Atlanta. But not pictures. Sure, there’s the the story from ancient Greece, of the contest between the painters Zeuxis and Parrhasius, when the painter Xeuxis painted grapes that were so realistic the birds swooped down to try to eat them? But I don’t believe it. I don’t think animals and birds do understand pictures.

Except maybe of eyespots.

Update January 7th 2010! Turns out I’m wrong about animals – dogs anyway – and pictures! Read on for the details.

Continue reading →