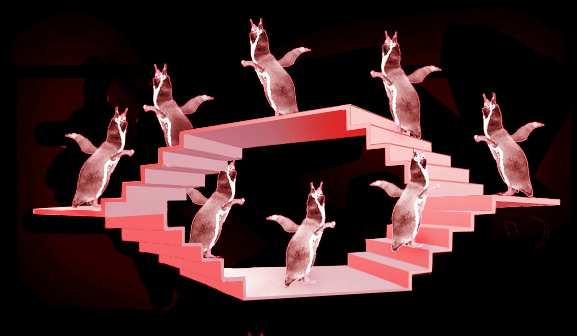

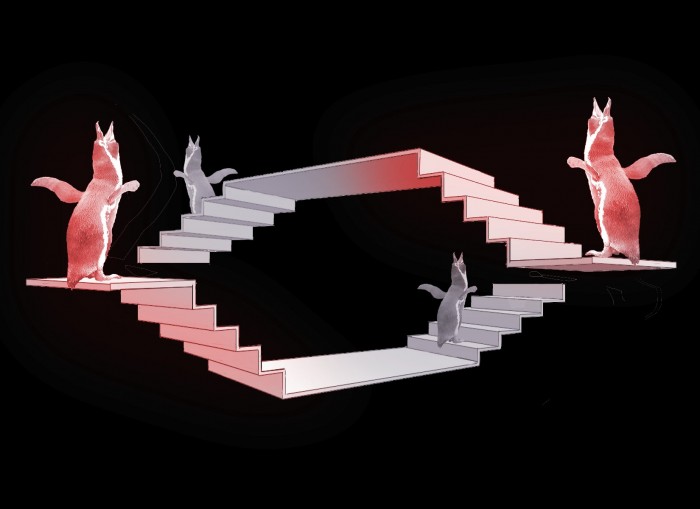

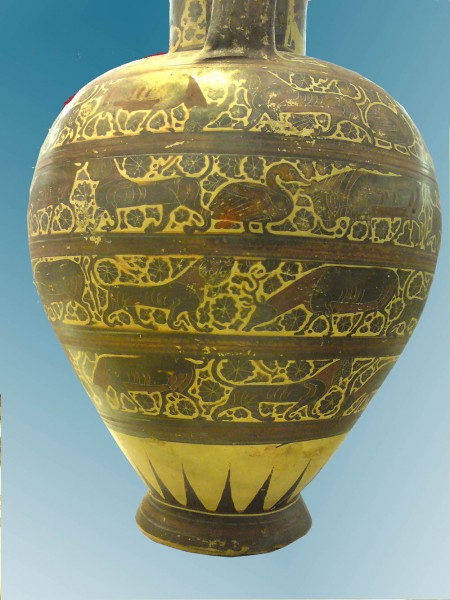

I wrote in an earlier post about how effective decorative motifs can be if they are ambiguous visually or in some other way a bit of a challenge for perception. Why that should be is a mystery, but here’s another of my favourite examples, decoration from a pot made in Corinth, Greece, about 595 BCE.

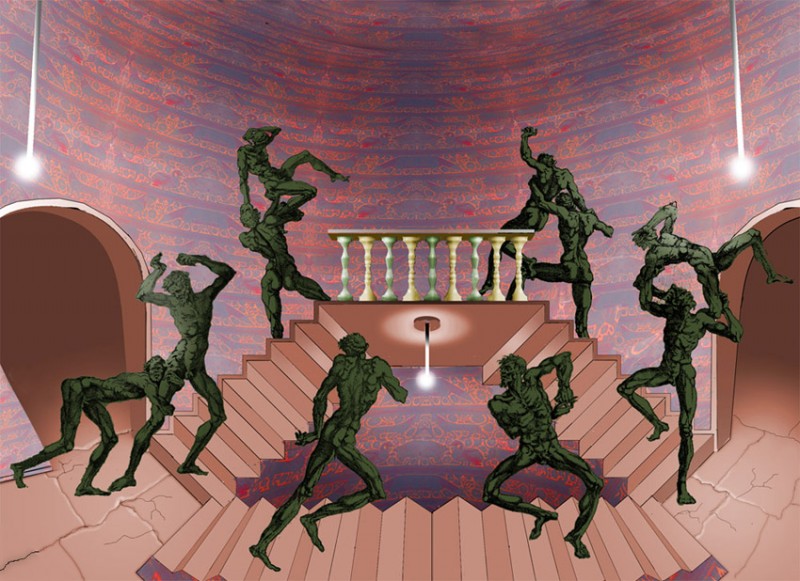

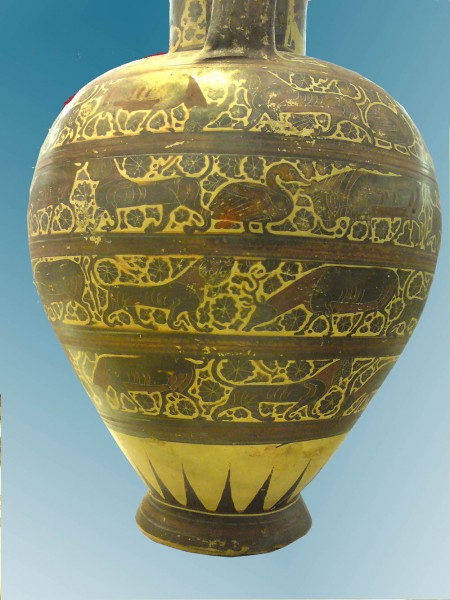

The pot’s in the British Museum and I guess it’s about 70 cms high. Here’s (nearly) the whole thing.

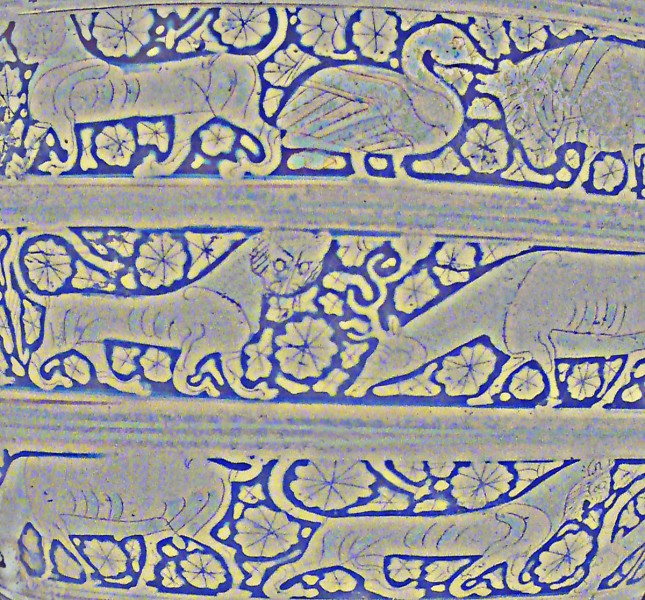

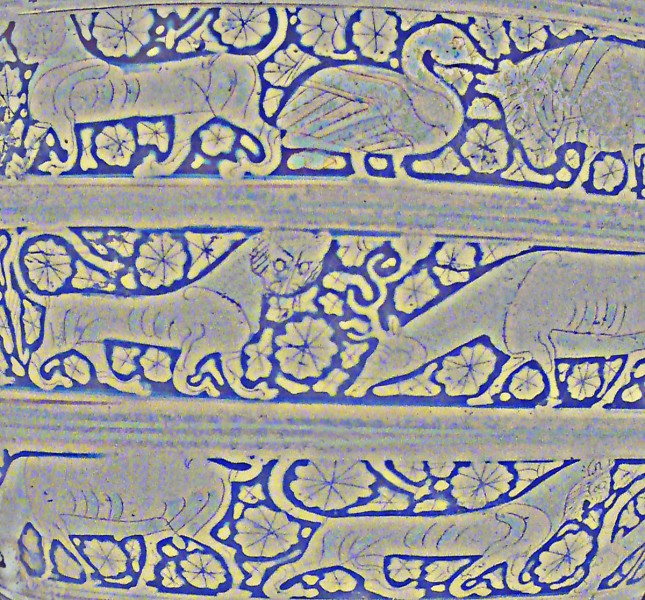

What’s unusual about this decoration is the way the rosettes and other little decorative motifs in between the animals have expanded to fill almost all the space. In earlier Corinthian decoration, they were much smaller, just little motifs floating in the pale space round the animals. Over two or three decades, painters made them fill more and more of the space, until they left only an outline round each animal. I reckon that shows up better in a version of the first picture which I’ve played around with, and reversed so that the pale outlines are dark.

What’s perceptually puzzling about that, I reckon, is that the brain can’t quite decide whether, in this reversed version, these are animals with strong, dark outlines on a pale background, or pale animals silhouetted on a dark background. If you like doing your own paintings, it’s a brilliant effect to play with, and works just as well with modern motifs, human figures, cars, aeroplanes, umbrellas, you name it.