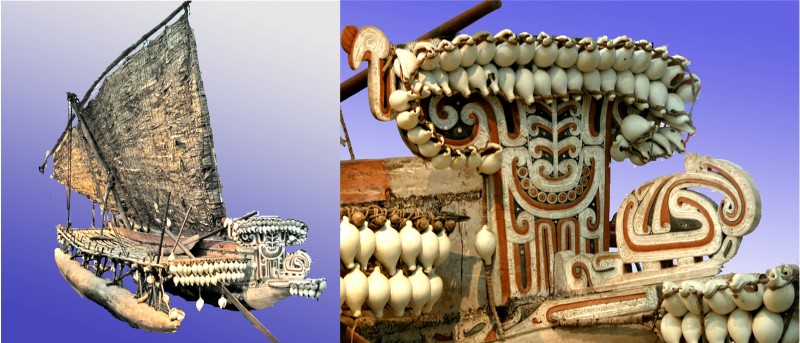

This wonderful ornamental canoe prow represents some fabulous creature, looking to the right. Prows like this appeared on boats used in a cycle of trade around the Trobriand and nearby Islands in the Western Pacific, called the Kula trade. The wonderfully ornamented canoes were only a small part of the story of this cycle of trading, but an intriguing one: the idea was to contrive a canoe so visually baffling that as your fleet of canoes approached the beach, it left your trading partners too bemused to compete in bartering. (For a more detailed account, if you fancy a bit of fairly heavyweight anthropology, there’s a fascinating essay by Alfred Gell called The Technology of Enchantment, in a book on art and anthropology from 1992).

The canoe prow is in the museum in Liverpool, UK, but to see a whole canoe go to the museum in Adelaide, Australia. It doesn’t have quite such a splendid, baffling prow, but it does show what these fabulous boats were like.

If you’d like to know out why these canoe prows remind me of paper marbling, read on.

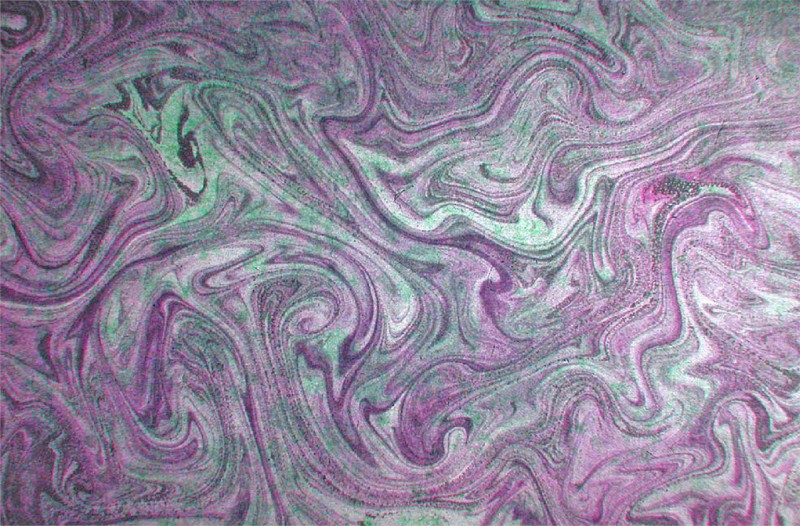

I reckon one of the reasons prows like the one in the picture at the start of the post are so striking is because they bamboozle the way we usually make visual sense of the world. They do that because every part of the pattern seems to flow into every other part. Our brains are looking for objects we can enclose in closed outlines, (there’s an earlier post of that), but there aren’t any closed outlines here. And that’s why the canoe prows are like 19th century paper marbling of the kind in this picture.

These patterns are rather like the irridescent ones you see when bright light reflects from a layer of used motor or cooking oil on a smooth water surface. The patterns on paper were made by first getting them to appear in inks on the surface of a mixture of water and glycerine, and then lifting the ink off on paper – a very tricky business. To my eye what makes them so beautiful is the way the pattern won’t settle down, because we can’t find closed outlines as a first step for making sense of what we’re seeing. As in the canoe ornament, everything pretty much flows into everything else. I don’t know why puzzling images should so often be beautiful, but visual puzzlement does seem often to be a useful first step in contriving a beautiful image. I’m so interested in that that I have a whole category of the site devoted to it).

Notice the mushroom shape bottom left. That’s a shape that often shows up in fluid surface patterns, most perfectly in whole glorious chains of interlocking mushroom shapes called Karman Vortex Streets.