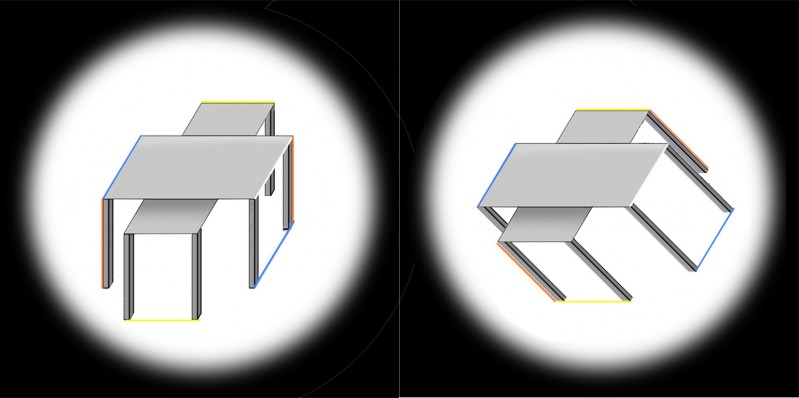

To view this illusion, you’ll need the knack of viewing 3D picture pairs without special spectacles, or a viewer – that is, by viewing them cross-eyed. If you haven’t got that trick, and want to try, start with one of our earlier posts on 3D.

If you do have the knack of viewing 3D pictures cross-eyed OK, you should see the pendulum apparently swinging in a circle. It’s MEANT to be a web-based demo of a famous pendulum effect you can fairly easily rig up in real life. It’s called Pulfrich’s pendulum, after researcher Carl Pulfrich, who published it in 1922. (NB! Faulty videos replaced at 31/10/15)

Here’s how it should work in real life. You hang up a pendulum, say two meters long, but so that it can only swing from side to side – it must not be free to swing backwards and forwards at all. (Details below on a low-tech way of doing that). You place a reference object under the pendulum, (I use a candle stick), so that the swinging pendulum just misses it, right at the mid-point of the swing. Then you view the swinging pendulum head on, but with a dark filter over one eye. All being well, you should see a really vivid illusion: the pendulum appears to swing not just from side to side, but in a circle. So it seems to swing alternately in front of, and then behind, the centre point marked by the reference object.

So why is my on-screen version here a fake? Read on to find out.

<!–more–>

The effect, in a real life demo, seems to arise because the brain takes longer to process the filtered, darker signal coming via one eye. The position of the pendulum at each moment therefore appears slightly different in each eye. The effect mimics the signal that would reach the brain if the distance of the pendulum from the eye was varying cyclically. The brain therefore infers that the pendulum is most probably swinging in a circle.

I thought it might be possible to imitate the real life effect with an animated stereo pair like the one below, but with one image much darker than the other. In fact, I now doubt it’s possible. Although on a screen one image can appear much darker than another, the strength of the apparent contrast is illusory. Measure the difference between the luminance from the lighter and darker images on-screen and it won’t be much. We see a strong contrast, because of the brain’s power to adapt to different levels of contrast. The difference in luminance from a real scene viewed with and without a dark filter will be far greater. But I thought it might work, and I tried the animation with every trick I could think of. And then suddenly I seemed to have got it. I was REALLY pleased with myself. I could even SEE the darker image as slightly delayed.

It was only the next day that I realised that what I’d done was accidentally to introduce a REAL time difference between the images, instead of an illusory one, arising from the difference in brightness of the pictures. Working in the animation software, (I use After Effects), I’d accidentally nudged an on-screen slider just a millimetre out of position. So what you are seeing here DOES demonstrate that it’s the timing difference that produces the 3D effect with Pulfrich’s pendulum, but you’re NOT seeing an illusory time difference due to brightness contrast. What you are also seeing is how easy it is to fool yourself (me anyway) when playing around with illusion effects.

There’s a really good Wikipedia entry on this effect, complete with details of some amazing 1990’s movie and TV uses of it, done with massive distributions of special specs!

Fancy trying to set up a pendulum yourself?

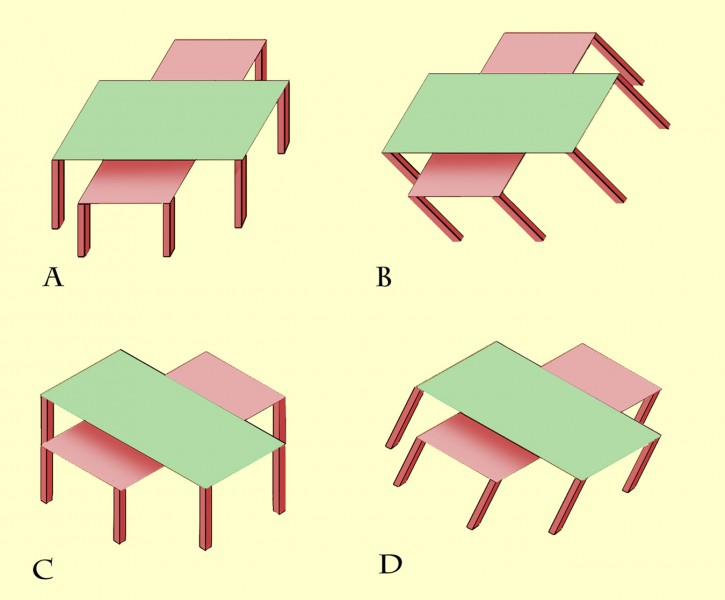

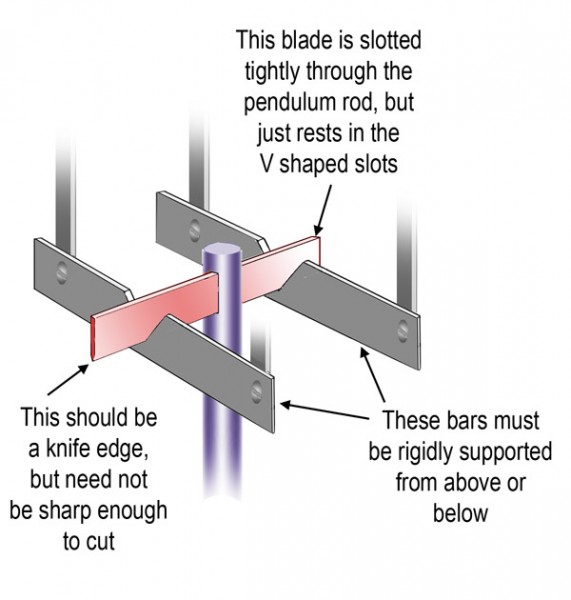

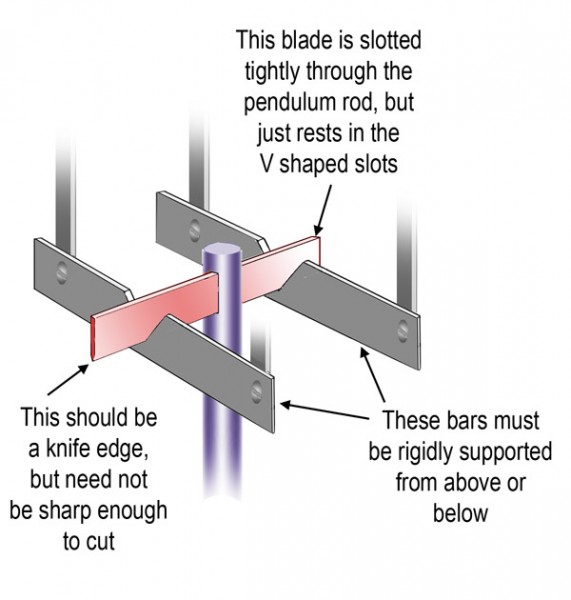

Fixing up a Pulfrich pendulum might be a bit tricky at home, but should be no great problem for a school science department. Here’s one low-tech design for a support armature that will only allow a pendulum to swing from side to side, within a plane, and not into depth. The support also avoids unnecessary friction, so that the pendulum swings for longer once set in motion.

The only other tricky part can be getting the dark filters, for one eye to look through. I believe sun glasses are usually not dark enough. I used dark the coloured acetate sheets usually supplied as colour filters for theatrical lighting. They should be available from a local theatre company (only a lens sized piece is needed) or a theatrical supplier. It’s a stunning demo!

If you wanted to experiment with animated versions, they do have one other virtue. You can get an idea of just how long the time lag has to be, in order for the illusion to appear. I found that with animations running at thirty frames a second, the lag could be no more than one frame! More than that and the two images of the pendulum remained separate. I guess with more frames per second, it would be possible to narrow down the time lag, but the maximum would seem to be about 30 milliseconds.