The illusion of movement when a series of images is animated is one we take for granted nowadays. However, here’s a small world first (I think) as new example. It’s a new Leonardo cartoon. Actually, there is a Leonardo cartoon already, THE Leonardo cartoon, in London’s National Gallery. But that’s not a movie. Art historians use the term cartoon for full size drawings for paintings. But now here’s another Leonardo cartoon, and this one is an animated movie. Maybe a bit short, that’s all.

Leonardo often made anatomical studies from viewpoints in a strict sequence as if moving round the specimen. Some years ago leading Leonardo scholar Martin Kemp pointed out that one famous set of studies, of the shoulder and arm with superficial muscles exposed, contains so many drawings it’s almost cinematic. In fact there are nine views, from three different sheets, which can just about be combined. The drawings are in the British Royal Collection. They have a great website, and here’s one of the Leonardo drawings, showing four arms.

Nine views is just barely enough for a slightly rapid animation.

Leonardo’s observation is so consistent that I only had to adjust overall proportions and contrast a little bit in some cases, in order to combine drawings from different series. It might be possible to make a smoother animation with more adjustment of the images, but I wanted to interfere with them as little as possible.

An effect that in some ways is even better is possible, with just the last two frames in the sequence.

For Leonardo in general, a fun site is the BBC one. The Wikipaedia Leonardo entry is very good too, with stacks of detailed info.

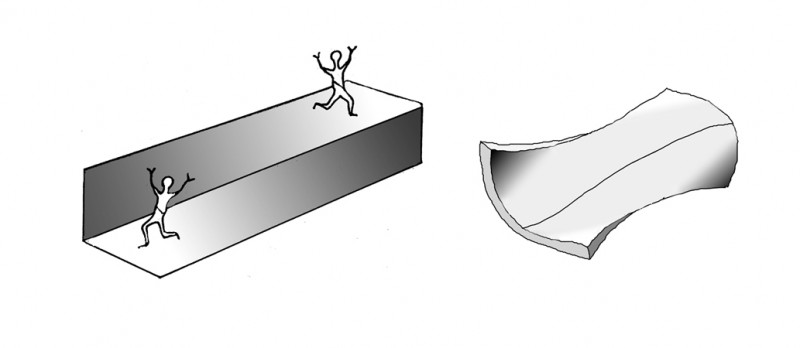

My short movie may be the first made entirely from a sequence of Leonardo’s own drawings, but it’s not the first based on individual drawings. Some brilliant, very professional animations were made from Leonardo drawings, for a show at London’s V&A museum in 2006/7. (I believe the animation was done by Aardman of Bristol). They developed their own sequences of images from individual drawings, of geometric shapes or machines, which they projected as 3D reconstructions, and then rotated and combined by computer. I’ve found only one example still on the WWW, but it’s a beauty, based on his drawings of the regular geometric shapes called regular solids.