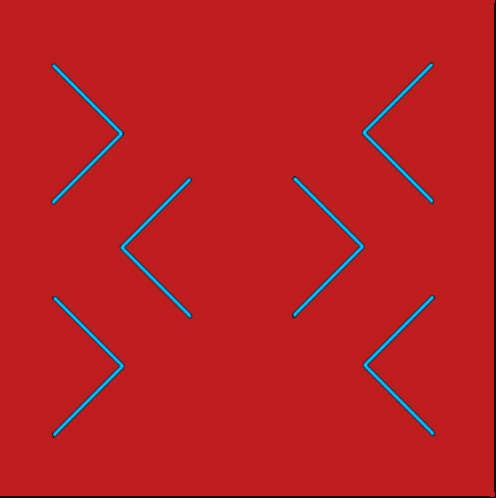

This is Morinaga’s paradox – two illusions in one, but two illusions that contradict one another. First note the vertical alignment of the arrow points. Don’t the tips of the inward pointing arrowheads, top and bottom, appear to be located just a little further inwards than the tips of the middle, outward pointing arrowheads? That could only be right if the horizontal space between the tips of the (top and bottom) inward pointing arrowheads was slightly less than the space between the tips of the (middle) outward pointing ones. But that’s not how it looks. The inward pointing arrowheads look further apart than the outward pointing ones.

In reality both judgments, of vertical alignment and of the horizontal gaps, are illusions. The tips of the arrows are perfectly aligned vertically, and the horizontal gaps between the three sets of arrowheads are all exactly the same. That last effect is a version of the Muller-Lyer illusion.

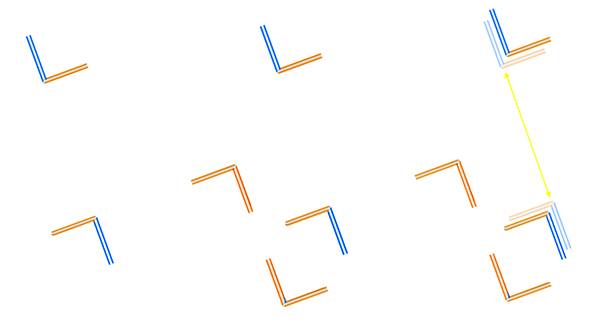

Here’s another paradox, also based on the Muller-Lyer illusion.

This can seem quite a subtle paradox, so let’s take it stage by stage. First look at the two left hand ninety degree angles. The blue arms are actually exactly aligned, but that’s not how it looks. It looks like, if you extended the lower blue arm up to the blue arm at upper left, it would intersect with the red arm. That’s a variant on the Poggendorff illusion, (or it is if you ask me – some say it’s a different illusion altogether). Now note that in the middle set of four right angles, the blue armed ones are repeated exactly as on the left, only this time as part of a version of the Muller-Lyer illusion, set at an oblique angle. The Muller-Lyer effect makes the inward pointing arrows seem further apart, and the outward pointing ones seem closer together. That would mean the the upper blue armed angle apparently moving upwards a bit, whilst the lower blue armed angle would have to shift down a bit. But if the blue armed angles had really shifted like that, the alignment of the blue arms would end up the opposite of what we observe, left and centre.

I’ve done a diagram version to the right, to try to demonstrate that. The ghostly angles mark the original positions of the blue-armed right angles. (The misalignment between the arms of the ghost angles has vanished, thanks to the yellow connecting line, which destroys any misalignment illusion). The real misalignment of the blue arms of the solid angles, shifted as if by the Muller Lyer effect, is now directly the opposite of the illusory misalignment we observe, left and centre.

Many illusions, like these, are distortions of the visual scene, as if our image of the world had been locally squeezed or stretched or twisted a bit. Sometimes the distortions seem to happen quite consistently, so that, for example, if one illusion squeezes one end of a pair of parallel lines together a bit, and another expands the space between them, the net result is that they end up looking about parallel. With other effects, as here, the distortion of one element in a scene (like the gap between the arrowheads here) can co-exist perfectly contentedly with a directly opposed distortion (like the misalignment effect here). We don’t yet have any clear idea of why there is a pecking order between competing illusions like this, with some co-existing paradoxically, as here, some fighting it out to a draw, and some even dominating others.